Autor: Igor Tretinjak /

Predstava Morphin’ izuzetno je mudra, slojevita, efektna te izvedbeno hrabra i zanimljiva studija odnosa izvedbenih i novih medija. Jedna od onih kojima bismo trebali dati prilike da igraju još i još

Neka od pitanja koja svako malo uznemire uspavane misli autora ovih redaka ona su kako otvoriti kazalište virtualnom svijetu i društvenim medijima te kako društvene medije „poturiti“ kazalištu, a da ne bude riječ o prvoloptaškim prikupljanjima osmijeha i lajkova ili o odricanju kazališta od živosti vlastite izvedbe. I dok vašeg autora te i takve more tek more, mlad, a već opasno zreo i promišljen autor i izvođač predstave Morphin’, Jura Ruža na iste nudi vrlo zanimljive izvedbene odgovore. Predstava, nastala kao Ružin diplomski rad na studiju neverbalnog teatra na Akademiji za umjetnost i kulturu u Osijeku, a danas dio repertoara varaždinskog Gllugla, čista je i jasna, i u toj jasnoći slojevita i mudra studija TikToka i njegovog utjecaja na naše tiktokizirane tikve, pardon, glave. Jasnoću joj osiguravaju čvrsta i čitka struktura te slojevitost neverbalnih i ostalih izraza iz kojih se gradi izvedba, a za ostalo se pobrinuo izuzetno uvjerljiv i scenski zavodljiv Ružin nastup. Pa krenimo redom…

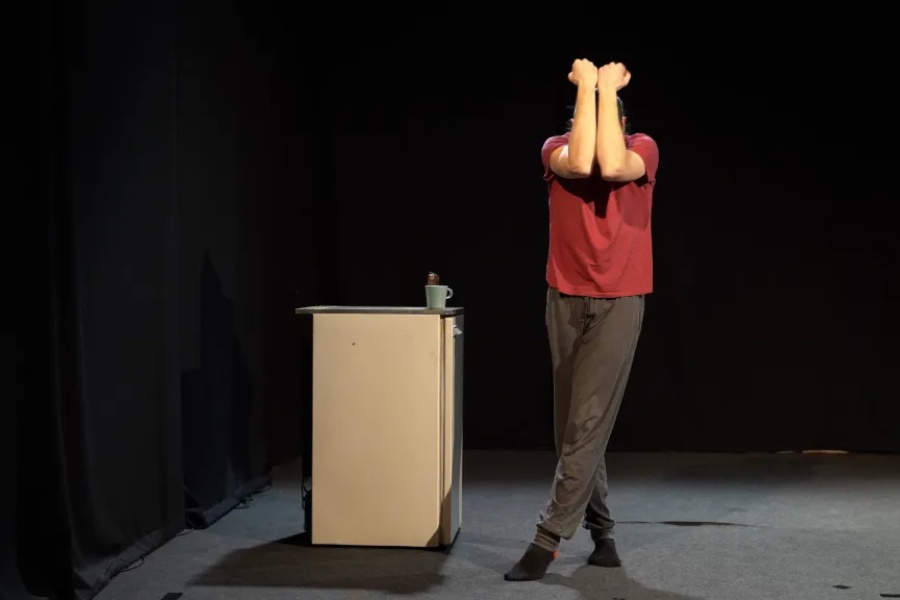

Predstavu otvara neverbalni dio u kojemu Ruža u savršenom miru i čistom zenu jede nevidljive pahuljice i bulji u nevidljivi mobitel u lijevoj ruci, stvarajući to savršenstvo mikro-svemira nepomućenim skladom između sebe i vlastite, lagano uzdignute i zgrčene, ljevice. Njihov odnos toliko je opipljiv da želimo prodrijeti u njega, odbaciti Ružu i postati dio tog sklada. To nam izvođač i omogućuje u sljedećoj sceni u koju se prelijeva dotadašnja nepomućenost. U njoj poziciju gledatelja zamjenjuje izvođačkom unutar nevidljivog mobitela, opetovanim pokretima sugerirajući kratke epizode i mrvice kulinarskih, fitness, ratnih i još pokojih svjetova koji gledatelja Juru zavode putem TikTok aplikacije na ekranu. Sve se u ove dvije scene gradi iz pokreta, dovoljno jasno da znamo kamo priča ide, ali i otvoreno da sami gradimo vlastite priče. Što je, dodajmo usput, sloboda koju, zalijepljeni za zadanost i opetovanost TikTok videa, nemamo.

Ruža, ipak, ne dozvoljava vlastitoj priči toliko osamostaljenje te minimalnom količinom riječi pojašnjava videa, kao da nije spreman u potpunosti ih prepustiti gledateljima. U isto vrijeme, uvođenjem verbalnosti u dotad neverbalnu predstavu ne ide za pukim pojašnjenjem u kojemu bi slika postala tek ilustracija izgovorenog, već riječi i rečenice ponavljanjem svodi na ritmove igre i mantre koje se duboko usijecaju u glave i misli publika. Riječi, ujedno, dolaze i kao gradacijski element te se neverbalna igra u suigri s njima zgušnjava i stišće, dok epizode u isto vrijeme polako gube samostalnost, prepliću se jedna s drugom, međusobno suočavaju, potom sukobljavaju, da bi se na kraju prelijevale jedna u drugu. Time gube smisao te postaju kaotična, a u tom kaosu ritmična, privlačna i zavodljiva, masa velikog ništa. No masa ne udara samo u sebe, već i u svog gledatelja (i izvođača). Vlastitom prepletenošću u nepovezanosti i bombom informacija koje to nisu ona ruši Ružin vanjski sklad i pretvara ga u buktinju energije koja se pretače u frenetični ples. Ta izvedbena kulminacija odlično ukazuje na buktinje besmisla što se skrivaju unutar početnog i tek naizglednog zena. Kad smo kod početka, povratak njemu i zatvara krug, no uz sitnu, no ključnu izmjenu – nakon frenetičnog plesa Ruža se za stolom bori za svaki dah, a kosa, dotad poslušno ukroćena u repu, leti u antenama na sve strane, pokazujući da ovaj ples s TikTokom u ruci i nije krug, već se spiralno uzdiže u kaos sadržajne i smislene praznine.

Jura Ruža stvorio je u predstavi Morphin’ izuzetno zanimljiv materijal u kojemu je vrlo elegantno, duhovito i pametno dramaturški izjednačio neverbalnost i verbalnost, animaciju dijelova tijela, igru s rekvizitima i zvuk koji su stvarale riječi te moćna i zavodljiva glazba (Arian Peharda) u sceni plesa, gradeći cjelinu svim tim elementima i njihovim međusobnim odnosima. Taj materijal dodatno je obogatio na izvođačkom planu, oblikujući cjelinu koja, usprkos opetovanosti, ne pada niti u jednom trenutku, štoviše, elegantno raste do usijanja i konačne poante. Učinio je to uvjerljivim, čvrstim, odlučnim, preciznim i ritmičnim pokretom (suradnica za pokret Martina Terzić), potencijalnu monotoniju elegantno izbjegavši sitnim pomacima i širenjem igre na dijelove scenografije poput frižidera i stola. U isto vrijeme, vlastiti scenski dijalog s mobitelom, društvenim mrežama i TikTokom na suptilan je način otvorio prema publici, uvukavši je u igru sugestivnim i moćnim pogledima kojima je stvarao tihe, strpljive i umirujuće dijaloge s pojedincima, pokazavši izvedbenu zrelost i sugestivnost.

Na kraju red je da, na tragu Ružine predstave, zaokružimo ovaj osvrt i vratimo se na sam početak. Kako, dakle, Jura Ruža vidi susret izvedbenih umjetnosti i društvenih medija, točnije TikToka? U Ružinoj predstavi TikTok je u isto vrijeme početni motiv, tema i izvedbeni materijal, prostor teatra unutar teatra te protagonistov partner, suparnik, antagonist, a u nekim trenucima i protagonist sam. Taj slojeviti odnos s društvenom mrežom kao predstavnicom novih, virtualnih medija, Ruža oblikuje starim, dobrim fizičkim teatrom, odnosno vlastitim tijelom. Sve to i još koješta što sam prešutio ili previdio, potvrđuje moju početnu premisu kako je predstava Morphin’ izuzetno mudra, slojevita, efektna te izvedbeno hrabra i zanimljiva studija odnosa izvedbenih i novih medija. Jedna od onih kojima bismo trebali dati prilike da igraju još i još.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.